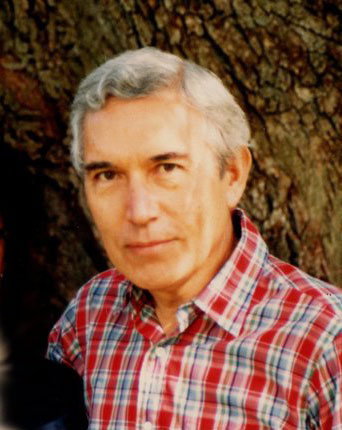

Remembering John Ferrone who died 4/10/2016

Anaïs Nin introduced me to John Ferrone, her Harcourt Brace Jovanovich editor, at her Silverlake, California house where she lived as the wife of Rupert Pole. John, a New Yorker, knew her other husband, Hugo Guiler, as well, and was privy to the secret of Anaïs’ double life. As one of the most grace-full men I have known, both in his manner and his movements, he was at ease in the world of sexual/emotional discretion. He’d lived the life of an undisguised gay man of 1950’s New York, and it was a world he negotiated with integrity and subtlety.

Anaïs Nin introduced me to John Ferrone, her Harcourt Brace Jovanovich editor, at her Silverlake, California house where she lived as the wife of Rupert Pole. John, a New Yorker, knew her other husband, Hugo Guiler, as well, and was privy to the secret of Anaïs’ double life. As one of the most grace-full men I have known, both in his manner and his movements, he was at ease in the world of sexual/emotional discretion. He’d lived the life of an undisguised gay man of 1950’s New York, and it was a world he negotiated with integrity and subtlety.

In 1978 when I published my first book The New Diary in hardbound, John made an offer to my publisher, Jeremy Tarcher, for Harcourt to acquire the paperback rights. Although he was contractually obligated to inform me of the offer, Tarcher without my knowledge rejected the Harcourt offer out of hand. When later I learned from John that he’d made the trade paperback offer while no one had told me, he was outraged. He was a genteel literary editor, a breed that has all but disappeared, a man of honor who pledged his impressive gifts to enhance the work of his authors and stay in the background. He was modest about the vast improvements he made in Anaïs Nin’s prose.

Anaïs, who most valued spontaneity in writing, once told me dismissively flicking her fingers, “Punctuation, grammar, that’s for editors.” John did far more than correct her unschooled grammar and punctuation, though. He highlighted the intelligence and emotional wisdom in her outpourings while giving her work an aesthetic subtlety it would otherwise lack.

Because of his commitment to make Anais’ writing shine in the best light, John’s relationship with Rupert became antagonistic after her death. Each man complained to me about the other. Rupert wanted to preserve Anais’ every word as she wrote it. He was working with John on Harcourt’s publication of her posthumous erotic work. John was dedicated to making her writing as honed as possible, which required cutting and shaping. They both loved her and her memory and, as with so many people who have loved her or her work, felt an almost irrational exclusive ownership of her.

Yet on another occasion I recall an evening when John and Rupert were as jovial as two teenage buddies together. I was then in my 30’s and working as President of Grand Central Films, a co-venture between Thames Television and an American production company. I wanted to option the Diaries as a network television mini-series. Since John was visiting L.A. and I then had an unlimited expense account, I invited John and Rupert to an expensive trendy restaurant near Paramount. They were adorable, each vying to be the most charming and witty, like competing beaus. Anaïs was gone, but her flirtatious spirit was with us that night.

In later years I would phone John when I visited New York and he would always make time to take me to lunch or dinner or, even better, cook for me. We both enjoyed literary gossip and swapping stories about Anaïs’ foibles and secrets. He was lonely after his partner died, and for such a reserved gentleman, warm and vulnerable when he talked about the importance – the centrality – of love in our lives.

I recall only one disagreement between John and myself; it was just a half-full/half empty difference in perspective. I had been admiring Anaïs’ tenacity in working on herself, in transforming herself from a neurotic, frustrated unpublished writer into a joyous woman who shared her hard-won success and wisdom with others. John bemoaned that Anaïs enjoyed the publication of her Diaries and her emotional equanimity so late in her life. “She only had a few years before knowledge of her cancer ruined it,” he said, “It took her so long to get what she wanted. She enjoyed it so briefly.”

“But she got there. She realized her dreams,” I said.

He shook his head. “Too briefly.”

I understand those feelings now, John. You had a relatively long life, living despite Parkinsons Disease to 91. My regret is that our friendship blossomed only in your later years and lasted too briefly, too briefly.